Why Africa should look to India for digital inspiration

5 Africa’s digital economy is still small in size compared with those of its global peers. But it has seen exponential growth over the past decade and now has the potential to redefine the continent’s economies. Africa had the fastest growth in internet access of the world’s regions between 2005 and 2018, from just 2.1 percent of the population to 24.4 percent. It is home to the fastest-growing mobile phone industry, with 20 percent annual growth between 2005 and 2017. It is estimated that half of Africa’s population will have a mobile phone subscription by 2025.

Even so, immense challenges must be addressed to ensure that Africa’s digital ecosystems are positioned to support the employment growth the continent needs. African governments and development finance institutions (DFIs) should look to India as a model and focus on critical infrastructure needs. This includes reducing the cost of data and increasing access to fixed-line broadband, spurring corporate ventures in the tech ecosystem, and providing Africans with the skills they need to take part in this digital transformation.

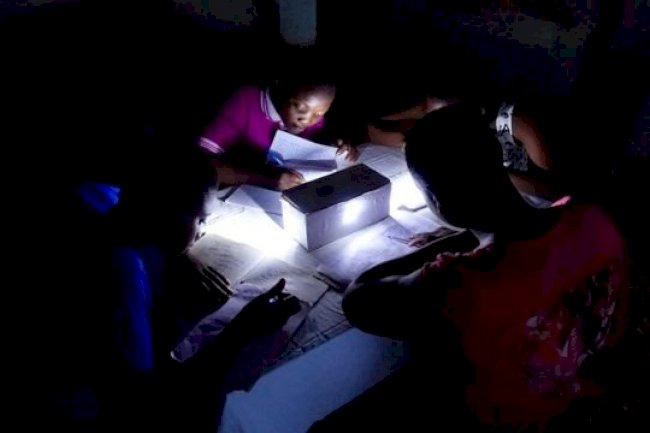

The lack of adequate access to the internet in most African countries boils down to the fact that mobile data is too expensive and fixed-line broadband is too slow and not widely available. It costs Africans on average $7.04 or nearly 9 percent of their monthly income for just 1GB of mobile data (enough to watch about three hours of low-quality video on Netflix). That compares with just 3.5 percent of monthly income in Latin American and 1.5 percent in Asia. There has been progress in some countries. In Nigeria, mobile data prices continue to drop following a decision by the Communications Commission in October 2015 to remove a floor on data prices, and increased competition among submarine cable companies. In India, competition among carriers played a critical role in lowering mobile data costs, which are now the cheapest in the world. Reliance Jo, a young telecom operator, is highly responsible for the shift, investing $35bn in a 4G network and offering free unlimited data trials to attract new customers.

While some have criticised the company’s practices and data prices may increase, the impact of private sector investment and competition has benefited average Indians. African governments should further liberalise their telecoms sectors and encourage competition to promote private investment in infrastructure that can be shared by providers. Regulators should track the cost of data as a measure of the healthiness of the industry. Beyond mobile data, African countries must increase the speed of fixed-line broadband internet and further improve access. A report by cable.co.uk measuring countries’ fixed-line broadband speeds showed zero African countries meeting speeds above 10 Mbps, the deemed minimum speed required by consumers. Such limitations are problematic for Africa’s growing tech hubs and ecosystems, where internet speed is cited as a limitation for start-ups and customers. While some African countries, such as Kenya, have greatly increased the speed of mobile data, businesses are going to need faster speeds to accelerate growth. As Africa builds its digital infrastructure, entrepreneurs and tech businesses need quicker access to funding. While numbers vary, WeeTracker reports that $725.6m in venture capital was invested in 458 deals in 2018, a year-over-year increase but still tiny in comparison with global peers. Africa has 618 tech hubs today, with Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa and Egypt leading the way. DFIs, governments and venture funds were key to spurring the first wave of tech hub growth across the continent, but without increased investment and the professionalisation of incubators and accelerators, African start-ups will continue to fall short. Despite hundreds of hubs (of which about a quarter are solely co-working spaces), start-ups are short of corporate partners to help with the challenge of scaling on a continent with non-traditional supply chains, difficult distribution and limited access to financial markets. In India, corporate venture from companies such as the Times Group and Microsoft (which has invested in 134 start-ups in the country) not only helps fill a funding gap but also plays a vital role in supporting companies, from sharing manufacturing plants to best business practices. Forty per cent of venture deals in Asia involve a corporate partner, helping to spur an ecosystem that could be replicated in Africa. Hybrid corporate-government/DFI venture capital models could be used to support increased investment from global tech companies less familiar with the continent and with a lower risk appetite. Companies also increasingly recognise the need to train talent on the continent. Without greater commitment to raising African’s digital skills, countries run the risk of falling behind in digital transformation, and in attracting enough capital for African businesses and entrepreneurs. DFIs should prioritise investments in digital infrastructure and quality education.

Today, less than 25 per cent of Africans earn Stem degrees in higher education. Government commitments are needed to increase the number of Stem graduates and to invest in basic digital literacy. Rwanda’s National Digital Talent Policy offers a model for targeted upskilling across the breadth of society, from creating “Smart Classrooms” at the elementary school level to offering more niche tech degrees in fields such as network engineering. DFIs should look to invest in companies such as Andela or Lambda Academy, a start-up online coding boot camp that expanded to Africa in 2019 to offer training in software development through a partnership with Nigerian fintech start-up Paystack. Developers receive their training from offices in Africa and pay no fees for the programme if they take a job with one of the academy's partner companies in Africa. Many of these developers will start their own companies locally or continue to work for African companies, keeping vital talent on the continent. Governments and DFIs need to look for models such as these that balance upskilling with the risk of brain drain. India has taken steps to tackle this; even before the Trump administration introduced visa restrictions, India saw a reversal of brain drain with hundreds more scientists returning home to pursue research than in previous years thanks to growing tech opportunities at home. Programmes that pair education with employment could help African countries to stem the outflow of tech talent. Like India, Africa is home to a young, urbanising, often mobile-first population. Of the 1.3bn people in India, 50 percent are under the age of 25. In Africa, 60 percent of the continent’s 1.25bn people are under 25.

The number of megacities will continue to grow for both. Their respective populations tend to turn to mobile and prefer video, evident in the early adoption of mobile money and the popularity of websites such as YouTube. India, unlike China, Korea or Singapore, is a large federal democracy — a more relatable model to the challenges Africa faces than Asian counterparts. While by no means replicas of each other, India’s digital transformation serves as a better model to understand how Africa can digitally transform and compete globally. Without dedicated national and regional strategies to address needed changes, African countries risk falling deeper into the digital divide.

Aubrey Hruby is a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Africa Center and co-author of ‘The Next Africa’ (2015). beyondbrics is a forum on emerging markets for contributors from the worlds of business, finance, politics, academia and the third sector. All views expressed are those of the author(s) and should not be taken as reflecting the views of the Financial Times.

Source: FT.com

What's Your Reaction?